Re: The death of the corporate job. (Alex McCann of Still Wandering)

The Great Irony of The Great Pretending.

A couple days ago Alex McCann wrote a popular piece about the performative nature of the corporate world that everyone just keeps going along with. He dubbed it the Great Pretending. After three years of deliberation, I finally quit my job this June largely for the reasons he describes, but also for something he doesn’t really get into. Today I reply with the Great Irony.

Being the kid of a revolution, I have always felt what Emmaly Perks describes as “chronic misalignment between their inner world and the structures of traditional workplaces.” The best way I can describe this feeling is seeing each day with fresh eyes and purposefully rejecting the order that everyone else agreed on while I was asleep. It’s part autism, part narcissism, part bipolar disorder, part privilege, and part passed down generational trauma.

Everything is illogical, because humans are by default emotional

Walk the streets of Manhattan to see many illogical things. Homeless people sleeping beside empty homes. Hungry people watching others eat on outdoor patios. One restaurant with a two-hour wait line, while seven others on the same street sit empty. Groups of girlfriends complaining about finding the one, while playing too hard to get. A masked man just eating a whole jar of cheeseballs watched by thousands of people.

Maturing means learning about the social systems of friends and family, only to have it twisted by the realities of the economic system. Your genes, environment, experience, and knowledge will determine your ability to participate in these systems. Including handling all of their illogicalities under the guise of delusion.

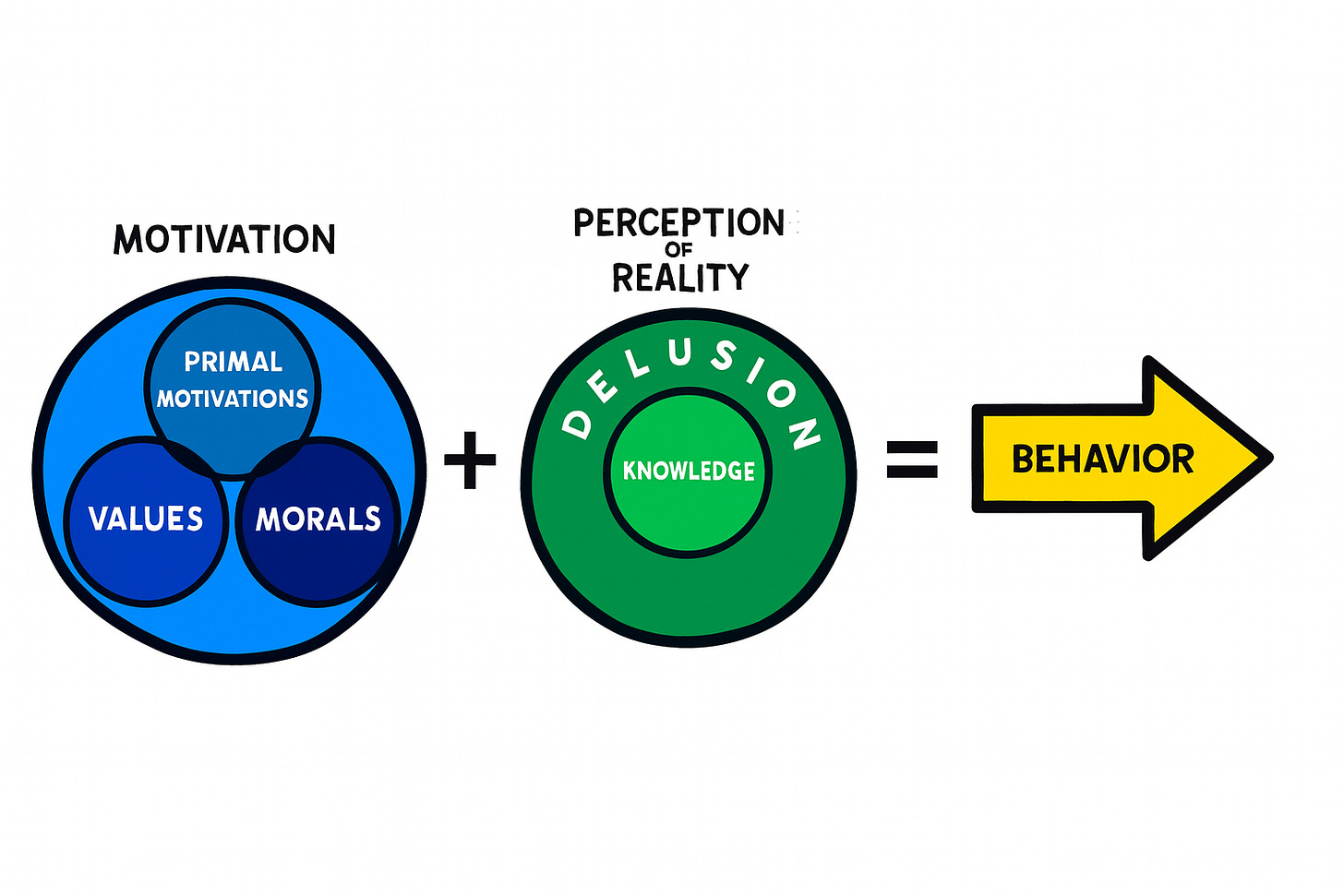

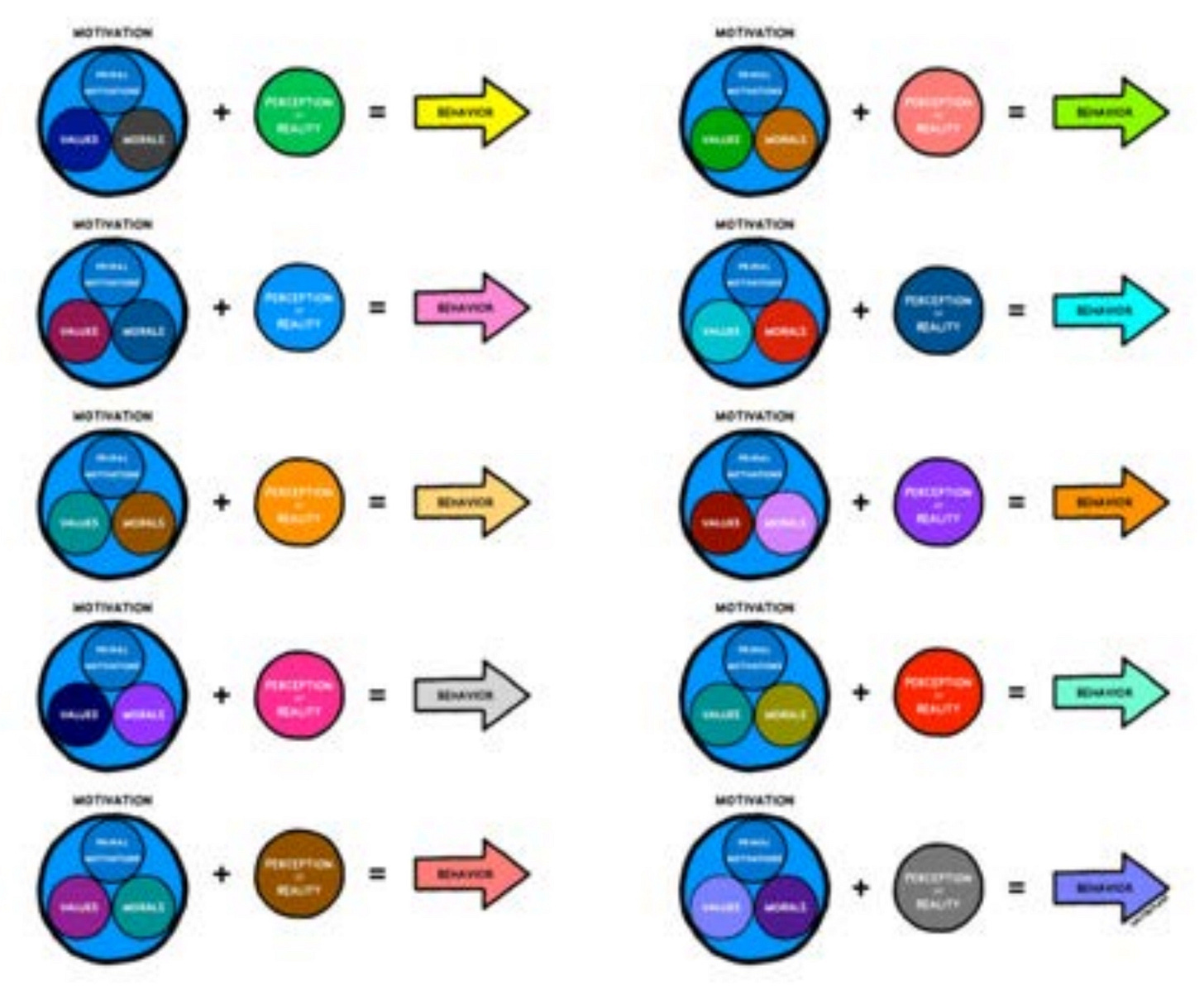

Tim Urban spent six years researching and illustrating this human conundrum in his now deleted blog series (but go buy his book). I’ll reuse his genius illustration to illustrate what I described above:

As you have already noticed in your life, there are as many of these versions, as there are environments and experiences, resulting in unique behaviors inside the different systems. Including as Alex puts it: “We've built entire ecosystems of mutual nonsense.”

I am then faced with the option whether I want to participate in the nonsense systems and live the American Dream of Patrick Bateman…

70% of workers are disengaged. Not unemployed - disengaged. Working but not really there. - Alex McCann

The concept of reskinning is native to the digitally native generations who grew up as avatars in video games, internet, and social media. Those who have mastered the conartistry of creating and shedding identities. It represents temporary, easy to replace relationships. It’s the moment you ask someone how they are doing, as they continue to zombie scroll through the infinity feed. In digital, or reality, they are “simply not there.” - from “The night Cinderella died”

…or choose something else.

Participating in the economic system is optional

After I quit my job everyone’s favorite question was: “but what are you going to do?” Which really is just politely asking how I’m going to survive. Without a steady job or a relationship I was labeled as “lost” — someone who’s searching for something that they are missing.

Go to any music festival and you’ll find your share of “lost” individuals.

The most common are the Employed who are living the escapist dream as their weekend identity. They are lost only temporarily and quickly found on Monday morning.

The Bohemians, who center their answers around ignorance of the economic system. This ignorance runs deep, often to what could easily be classified as trauma. I’ve heard attractive people, but especially women, rely on the kindness of strangers. I’ve met people living off disability checks from their government, odd lawsuits, or legacy money.

Then you have the less privileged Minimal Participants, who unwillingly do just enough to get by. Artists who offer to trade their work for a night’s sleep and a meal. Part time workers doing odd jobs to support or enhance their traveling and lived experience. This works especially well in tribal-like rural areas where people provide communal support and rarely a bullet to the head to strangers.

We cannot forget the anarchists, the libertarians, and the network state capitalists. People disillusioned by governance rather than the economic system itself, often over-rationalizing their own hunger for empowerment.

It should be a daily practice to view participation in the economic system as voluntary.

The uncomfortable truth is that we are all much better off by going along with the bit. The less fortunate majority is better off by living in this common agreed upon fantasy repeating the mantra: “That’s just the way it is” and “You got to do what you got to do.”

Fortunate people such as myself and the online discourse on Substack and Twitter might feel high and mighty, by pointing out the shortcomings of our times, but are just as much participants of our own pretense system. Writing publicly instead of in solitude, because we either seek validation, or an endless discussion, both ultimately just fueling our own narcissistic value system of self-importance.

The Great Irony

Instead of asking where we should draw the line with pretense, we should ask how we decide what counts as pretense. And we have a clear one word answer: value.

Sadly, just like the systems, there are plenty of values and to each person their own.

The economic system is of course structured around monetary value in the form of credit. David Graeber’s Debt continues to be my favorite read on this topic, highlighting how this standardized value exchange ties to cycles of violence, hierarchy, and morality. The book emphasizes that debt carries a moral stigma, but creditors (those who give money) often escape accountability while debtors are shamed. Unsurprisingly Graeber coined “we are the 99%” in his leading role of the Occupy Wall Street movement.

…the Value Games is what humans do when a key limitation is added into the environment: You can’t use a cudgel to get what you want. - Tim Urban

Value systems exist to protect us from killing each other. Challenging any of the systems has a high likelihood of violence and comes at a cost of morality.

Whether it’s leading a revolution against a dictator or defying the corporate leadership with new ideas, an individual or even a unionized group has always more to lose than gain. Not just monetary, but also in public perception or worse, as evidenced by whistleblowers. For further understanding we can turn to the Prospect theory in which people irrationally ignore math and prefer a guaranteed gain over a chance of higher gain.

In his essay, Alex argues that the generation just entering the workforce has been saved from ever participating in the Great Pretending, but really they have never had anything to lose:

Millennials, but mainly Gen Z, had their real identity exploited, opportunities stolen, and were indebted from education and property ownership. What’s left were the performative interchangeable identities used to prostitute, kill, or slave towards a dream that has long been broken. The American Dream has always been the absolute power fantasy. - from “The night Cinderella died”

Twenty-somethings memeify and cluelessly reject the corporate world due to its performative nature, and the mortgage generations refine their writing skills in viral pieces online, while they all run programs to appear online.

Pretending, however small, eventually accumulates into real consequences. Corporations sacrificing a great pretender like a scapegoat. Employees lazily shipping updates powering down the whole internet, or causing blackouts across the continent. Governments infiltrated by great pretenders to spy on national secrets.

The Great Irony is that the Great Pretending continues to have substantial effects on security, climate, finance, health, and defines the hierarchy of power. Until we find better alternatives on how not to kill each other over a loaf of bread and roof over our heads, we all better pretend.